What can be reviewed?

- Application source code

- Source code documentation

- Test code

- Design descriptions

- Requirements specifications Although this lecture focuses on source code review practices, a wide variety of project artifacts. Ultimately, any configuration item can be reviewed. Artifacts that are not controlled in this way should not be inspected, as it is not possible to track the consequences of change recommendations to the artifact.

Why Review?

- Detect defects in software

- Identify refactoring opportunities for poorly structured code

- Develop a shared understanding of code between developers

- Share good practice between team members

- Gain knowledge about legacy systems

The core purpose of code reviews is to detect defects and recommend improvements. However, it isn’t the job of the reviewer to actually make the changes. There are a number of other benefits of code reviews too. Shared understanding - collective ownership of code. This is known to improve code quality as developers want to impress their peers

But it is important to not use code reviews for incentives and punishments as this not longer boosts productivity, as it can cause tension in the team

When Code Review?

Code reviews, historically referred to as inspections, are opportunities for software developers to inspect a source artifact and recommend changes.

Historically, code reviews were referred to as inspections and took place periodically. Portions of a code base might be selected for inspection prior to a release for example, in order to detect defects and recommend their removal.

Modern code review is typically conducted on proposed changes to a code base following the creation of a merge request.

A code review may also be necessary if a team has adopted a legacy system. In this case, the goal will be to comprehend a portion of the code base before attempting a change.

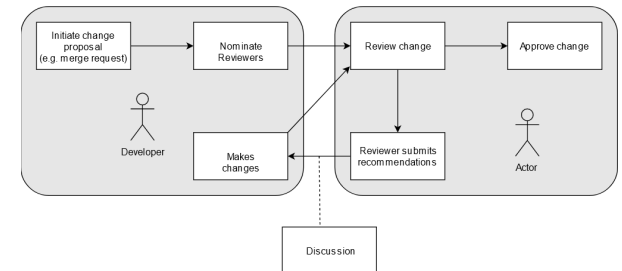

Code Review Workflow

- A change is proposed e.g. as a merge request, from a source branch to a target branch. The nature of the source and target will depend on the type of project. Small teams often maintain development branches within the master repository. Open source projects accept merge requests from branches in forked repositories.

- Reviewer(s) are selected from the rest of the development team. The team may have guidelines for this. Some modern tools can recommend reviewers based on different policies, for example, who has changed the affected artifacts most frequently in the code base. Many teams assume that reviewers should be at least as experienced as the submitting developer. However, there are benefits to having more junior colleagues conduct code reviews. This can help improve shared understanding of code, as well as eliciting new approaches to structuring the code.

- Reviewer(s) annotate merge request with recommended changes.

- Often very important/useful for developers and reviewers to have a follow up discussion about any recommendations. This can help clarify why the recommendation was made and what the reviewer is trying to achieve.

- Developer makes changes and re-submits merge request.

- Reviewer(s) approve merge request.

- Merge is applied by the developer.

Real-Time Code Reviews

Pair Programming

Pair programming involves two developers working together at one workstation. One, the “driver,” writes the code while the other, the “navigator,” reviews each line of code as it is typed. The roles are frequently switched. This technique enhances code quality and facilitates knowledge transfer among team members.

Mob Programming

Mob programming extends pair programming by involving the entire team in the code writing process. One team member acts as the driver, while the others observe and provide suggestions. This collaborative approach not only improves code quality but also ensures that knowledge and skills are shared across the team, leading to more cohesive and unified solutions.

Defection Detection Rate (DDR)

The Defect Detection Rate is a vital metric in software quality assurance that measures the effectiveness of testing processes in identifying defects within software components or methods. It provides insights into how thoroughly defects are being captured during testing, offering a quantitative assessment of testing efficiency.

Components of Defect Detection Rate:

- Total Defects: This represents the sum of all known defects across software methods or components plus any additional defects that have not yet been detected but are suspected to exist. The formula for total defects is expressed as:

\quad\quad\quad \text{total defects} = \bigcup_{m \in \text{methods}} \text{defects}(m) + \text{undetected defects}

\quad \quad \quad \text{defect detection rate(method)} = \frac{|\text{defects}(m)|}{|\text{total defects}|}

Here, $( |\text{defects}(m)|)$denotes the count of defects found in method $( m )$, and ( $|\text{total defects}|$) includes all identified and hypothesized defects. ### Importance of Defect Detection Rate: - **Assessment of Testing Effectiveness**: A high defect detection rate indicates efficient testing practices capable of uncovering a large portion of existing defects. - **Guidance for Improvement**: Tracking this metric helps pinpoint areas with lower detection rates, suggesting where to enhance testing efforts or focus development for quality improvements. - **Resource Optimization**: This metric aids in allocating resources more effectively by highlighting methods or components needing more rigorous testing. Overall, the defect detection rate is critical for evaluating and improving the quality assurance processes in software development, ensuring higher software quality and reliability. ## Do Code Reviews Work? [@fagan76design] reported a DDR of 66% and 82% for two IBM case studies employing a comprehensive inspection process. [@jones86programming] reported a DDR of 60% for design inspections alone, compared to a DDR of just 25% for unit testing. [@boehm81software] surveyed four case studies reported between 1978 and 1980, finding that inspections discovered between 63% and 75% of defects. [@wilkerson12comparing] found that inspections led to fewer defects left in a system than a test driven development approach to implementation. [@runeson06what] reported a more complex picture from a survey of 12 case studies. ## Good Practices for Merge Requests #### Keep Merge Requests Small - A single review should be of approximately 300 lines of code (max). - Should be possible to complete a review within ~30 minutes. - Break larger merge requests into smaller change packages. - Incorporate code review time into the team's workload model. Typical merge requests are from either: - A local branch in a repository on the server (small team projects) - A branch in a forked repository (open source projects) Google reported at ICSE 2018 that a developer spends approximately 3 hours per week conducting code reviews. #### Describing the Change - Give a succinct title. - Explain the purpose of the change - pick one of: - **Corrective**: Resolve bug reports and refer explicitly to the bug being fixed. - **Adaptive**: Responses to changes in a system’s environment. Example: Migrate to a new release of a dependency or language implementation. - **Perfective**: Add new features. State what the new feature does and refer to the requirement. - **Preventative**: Enhance the maintainability of code. Example: Refactoring. - Report wider impacts of the change, e.g., breaking changes. #### Automate Merge Requests Block merge requests that don’t conform to standards: - Maximum size - Breaking tests - Code style violations - Commented out code - Spelling mistakes - Inadequate tests - Utilize static and dynamic analysis to locate smells. - **Source code metrics**: Number of lines of code per function or module, the ratio between executable and comment lines of code. - **Design metrics**: Fan-in and fan-out coupling, cyclomatic complexity. - **Test suite metrics**: Test code coverage and mutation testing. - Usage pattern analysis can detect issues like memory and IO leaks or type cast errors. - Create a merge request template to ensure a consistent style. #### Questions to Ask During a Review - Does this change solve a problem? - How would I solve this problem? - Has dependent documentation, such as user guides, been updated? ##### Quality Assurance (QA) - What are the typical and extreme cases for the use of this code? Are they covered by test cases? - Has the developer thought about corner cases (empty collections, parameter boundaries, etc.)? - Are the test cases readable and well organized? - How does this code handle exceptional situations? ##### Architecture - Does the change follow the existing architectural convention for the software? - Are there missed opportunities for reuse of existing code? - Are there clones present in the change? ##### Code - Do identifiers follow project naming conventions? Is their purpose evident? - Is the code self-documenting? - Are all source comments necessary? ##### Non-functional Considerations - Are performance optimizations possible? - Are efficiency optimizations possible? - Are relevant security patterns followed?